How to Write a Biography About a Family Member: 11 Remarkable Tips

Writing a biography about a family member is one of the most meaningful—and misunderstood—forms of storytelling.

On the surface, it appears simple: You already know the person, you have access to memories, and you share history.

In reality, though, family biographies demand more rigor, not less. Why?

It is because proximity clouds judgment, memory distorts facts, and emotional attachment can weaken narrative clarity.

As a professional writer and biographical storyteller, I approach family biographies the same way I would approach a public figure’s life story: with structure, evidence, ethical discipline, and narrative intent.

The difference is in the responsibility.

This guide walks you through experts’ tips on how to write a biography about a family member, from defining purpose to shaping legacy, so your work becomes a lasting document, not just a sentimental record.

How to Write a Biography About a Family Member

Below are modern and relevant tips to help you effectively write a biography about a family member:

1. Start With Purpose, Not Memories

The most common mistake beginners make when writing a family biography is starting with memories.

Professional biographers start with a purpose.

Before writing a single paragraph, define why this biography needs to exist.

Purpose determines the scope of your research, the events you include or exclude, and the narrative lens you use.

Without it, a biography quickly becomes a collection of anecdotes rather than a coherent life story.

A family biography can serve several functions:

- Preserving generational or cultural history

- Passing down values and lived lessons

- Correcting silence, omission, or misinformation

- Honoring resilience, sacrifice, or achievement

- Creating a historical record for future readers

Your purpose acts as the biography’s thesis statement. Every chapter should support it.

Expert Tip

If you cannot state the purpose of your biography in one clear sentence, the narrative will lack focus and authority.

Example Purpose Statements

- To document my grandmother’s role in sustaining our family through economic hardship.

- To preserve my father’s life story as a first-generation immigrant for future generations.

- To humanize a family member whose life has been reduced to rumor or misunderstanding.

Purpose comes before memory. Memories supply texture; purpose gives the story meaning.

You can check out this article to learn how to freewrite with purpose in mind.

2. Decide the Type of Biography You Are Writing

Not all biographies are the same, and professionals know this from the start.

Before drafting a single paragraph, decide what structural model best serves the story you want to tell.

This decision will shape not just the order of events but how readers experience and understand your subject’s life.

According to writing guides on biography structure, you can organize a life story in different ways, often choosing between chronological order, where events unfold from earliest to latest, and thematic order, where chapters explore big ideas or patterns instead of strict dates.

Common Biography Structures & When to Use Them

| Type | Focus | Best For |

| Chronological biography | Life events in order from earliest to latest | Clear developmental arc, historical accuracy |

| Thematic biography | Life organized around ideas (For example, courage, migration, service) | Legacy storytelling where meaning outweighs sequence |

| Memoir-style biography | Personal voice with reflection | Emotional impact and subjective experience |

| Cultural biography | Life examined in the context of society or community | Stories tied tightly to historical and cultural forces |

| Corrective biography | Focuses on correcting misconceptions | Truth-telling and reframing misunderstood lives |

Professional biographers often blend elements of these types to create a life story that is both true and meaningful.

While comprehensive interviews with well-known biographers are rare in simple online guides, most writing professionals agree on this core principle:

A biography should illuminate the subject’s life, not just list dates and facts.

Hermione Lee, a renowned biographer, supports this when he said:

This quote highlights that a biographer does more than just recount events — they must interpret them and craft a meaningful narrative.

Thus, choosing the right structure up front unfolds as a meaningful life story.

3. Treat Your Family Member as a Historical Subject

Closeness does not replace research.

In fact, it demands more verification, not less.

When writing a family biography, professionals deliberately step back and approach the subject as if they were a historical figure they never met.

This shift is essential.

As noted earlier, familiarity creates blind spots, while distance encourages accuracy.

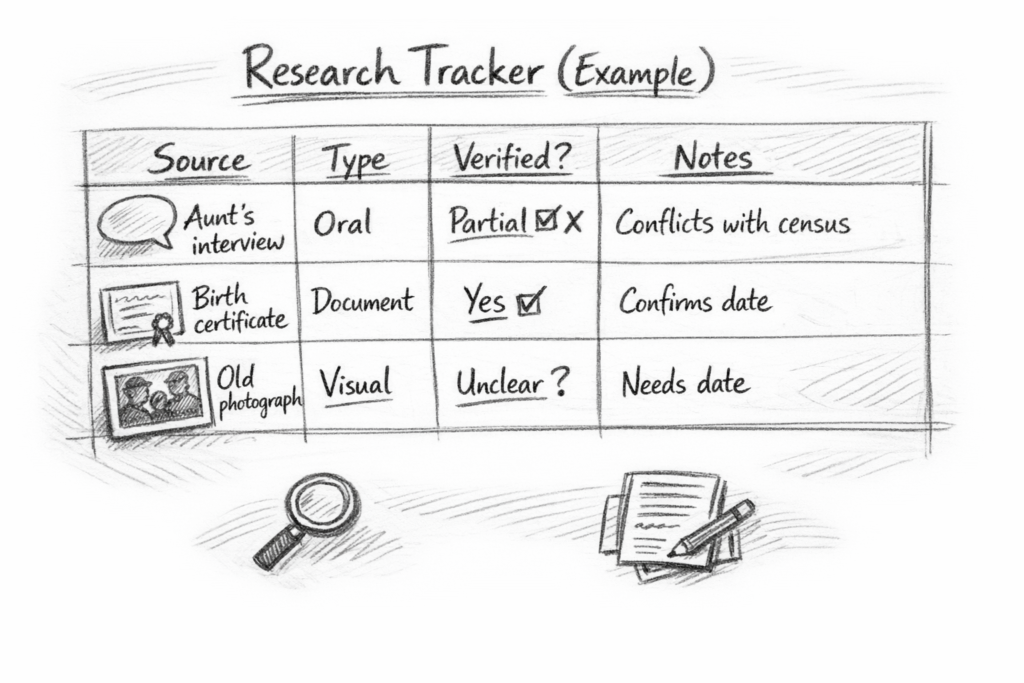

Biographical best practices emphasize that even intimate life stories must be grounded in documented evidence, not assumption or inherited memory—a standard commonly used in archival and historical research.

What Experts Collect

Professional biographers and family historians typically gather:

- Birth, marriage, and death records

- Letters, journals, and personal notebooks

- Photographs (with confirmed dates and locations)

- Educational, religious, or professional records

- Newspaper mentions, obituaries, or community archives

Oral histories are valuable, but they are never treated as the final authority.

They are compared against records, timelines, and additional testimonies.

4. Conduct Interviews Like a Biographer, Not a Relative

When interviewing family members, you must temporarily step out of the role of child, niece, or grandchild and into the role of biographer and historian.

Familiarity makes conversations easier, but it can also lead to assumptions, interruptions, and unchallenged narratives.

Professional biographers approach interviews with intentional distance. They listen for meaning, context, and contradiction—not validation.

Expert Interview Rules

To gather material that holds up beyond personal memory:

- Ask open-ended questions, not leading ones

- Allow silence—people often reveal more when they are not rushed

- Record interviews (with clear permission) to preserve accuracy

- Interview multiple people about the same events to capture perspectives

Avoid framing questions that suggest an answer.

- Avoid: “You were happy then, right?”

- Use instead: “How did you feel during that period of your life?”

This shift turns interviews from casual conversations into primary source material.

Pro Tip

Contradictions are not problems; they are evidence of lived experience. When two people remember the same event differently, the gap between their accounts often reveals emotional truth, power dynamics, or unresolved conflict. Skilled biographers use these differences to add depth, not confusion, to the narrative.

Conducted this way, interviews stop reinforcing family lore and start producing usable, credible history.

5. Address Bias and Emotional Proximity Honestly

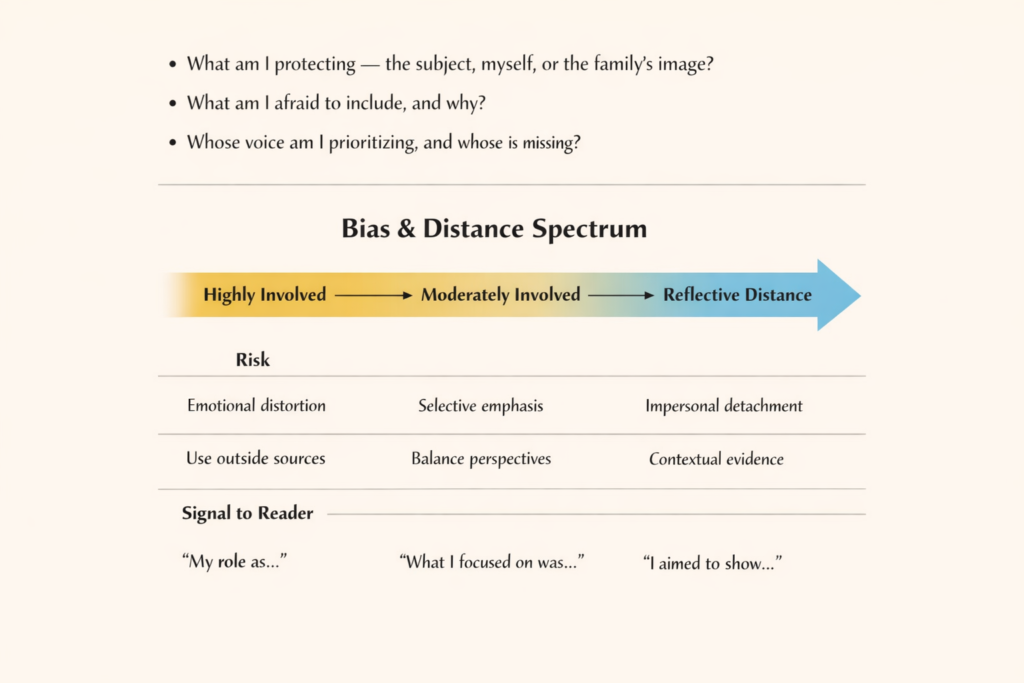

Every biography contains bias.

Experienced biographers don’t deny this; they name it, manage it, and write through it.

In family biographies, emotional proximity can quietly shape what is emphasized, softened, or avoided altogether.

Before drafting, interrogate your position as the writer:

- What am I protecting? The subject, myself, or the family’s image?

- What am I afraid to include, and why?

- Whose voice am I prioritizing, and whose is missing?

A credible family biography does not sanitize or idolize its subject.

It humanizes them.

Readers trust work that acknowledges complexity over work that performs reverence.

When addressing sensitive material such as addiction, estrangement, or failure, professionals focus on context and consequence, not exposure. You can:

- Provide necessary background without graphic detail

- Emphasize impact rather than accusation

- Use reflective distance instead of moral judgment

Bias Disclosure Note

Consider including a short author’s note explaining your relationship to the subject and your approach to difficult material. This transparency strengthens credibility and signals ethical intent.

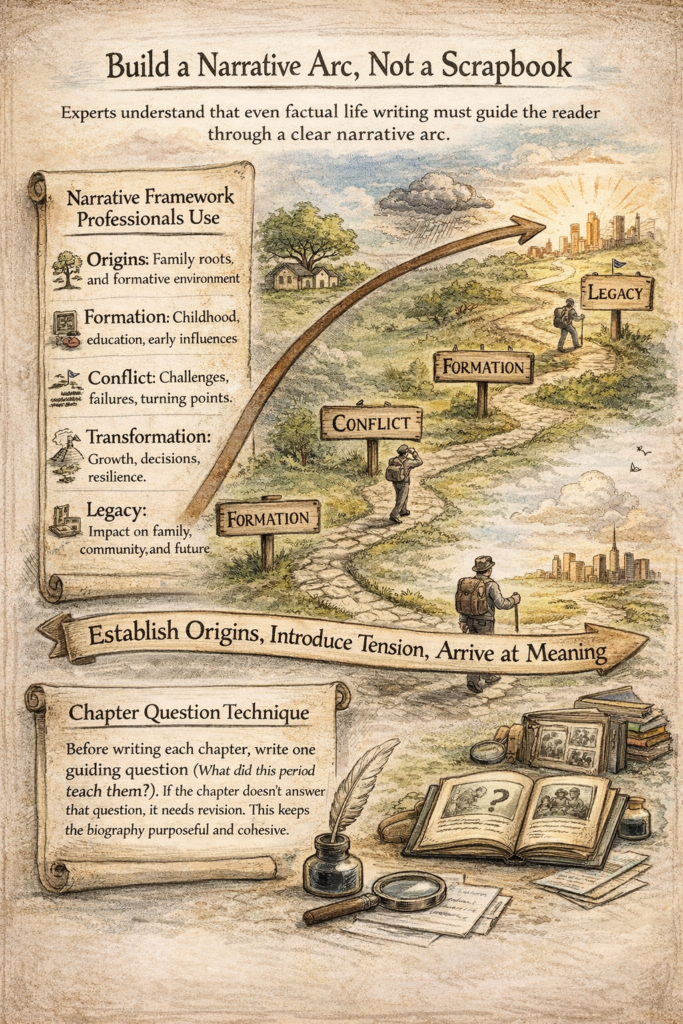

6. Build a Narrative Arc, Not a Scrapbook

Experts understand that even factual life writing must guide the reader through a clear narrative arc.

Strong biographies move with intention.

They establish origins, introduce tension, and arrive at meaning.

Without this structure, a biography risks becoming a scrapbook: emotionally rich but narratively unfocused.

Narrative Framework Professionals Use

- Origins: Family roots and formative environment

- Formation: Childhood, education, early influences

- Conflict: Challenges, failures, turning points

- Transformation: Growth, decisions, resilience

- Legacy: Impact on family, community, and future

This framework allows readers to understand not just what happened, but why it mattered.

Chapter Question Technique

Before writing each chapter, write one guiding question (What did this period teach them?).

If the chapter doesn’t answer that question, it needs revision. This keeps the biography purposeful and cohesive.

7. Situate the Life Within Its Historical and Cultural Context

A family biography gains authority when it clearly acknowledges time and place.

Lives do not unfold in isolation; they are shaped by social norms, political forces, and economic realities that expand or restrict personal choice.

Professional historians emphasize that individual stories only become historically meaningful when placed within their broader context.

As the U.S. National Archives explains, historical records gain value when they are interpreted within the social and institutional conditions in which people lived and made decisions.

When writing, ask:

- What social, political, or economic conditions shaped this life?

- What norms limited or expanded their choices?

- What forces were invisible to them but decisive in hindsight?

For example:

- Migration stories require a policy, labor, or opportunity context

- Women’s lives must reflect the gender expectations of their era

- Economic hardship should be framed within wider systems, not personal failure

This approach transforms a personal narrative into a historical document, allowing readers to understand not only what happened but also why it unfolded the way it did.

8. Use Scenes, Not Summaries

Generic biographies summarize. Expert biographies recreate moments.

A summary tells readers what happened; a scene allows them to experience it.

Writing educators consistently stress that scene-based storytelling is what gives nonfiction narrative credibility and emotional resonance.

As MasterClass notes in its biography-writing guidance, strong biographies rely on concrete scenes to bring real lives to life on the page.

- Instead of: “She worked hard to raise her children.”

- Use: “She woke before dawn, kneading dough by candlelight, so her children would eat before school.”

Scenes anchor memory in sensory detail, sound, movement, and setting, and make claims about characters believable rather than abstract.

Expert Rule

Every chapter should contain at least one fully rendered scene grounded in observable detail. Scenes do the work that adjectives cannot.

9. Include Reflection Without Dominating the Story

If you appear in the biography, do so intentionally, not instinctively.

Your presence should clarify meaning, not compete with the subject.

In professional life writing, the author’s role is often defined as one of three positions:

- Observer: Recording and contextualizing events

- Interpreter: Explaining significance and patterns

- Custodian of memory: Preserving stories for future readers

Avoid centering your emotions unless they directly help the reader understand the subject’s life or legacy.

Writing guides on memoir and biography repeatedly caution against letting reflection overwhelm narrative, noting that restraint builds trust.

Expert Balance

Reflection explains why the story matters. The subject remains the focus.

When used carefully, reflection becomes a lens, not a spotlight, and strengthens the biography’s authority rather than diluting it.

10. Edit With Distance and Discipline

Expert biographers understand that first drafts are for discovery.

However, revision is where authority is built.

Editing a biography is not a single pass; it happens in deliberate stages, each serving a different ethical and narrative function.

Professionals typically revise biographies in the following order:

- Structural edit: Does the story flow logically? Are events arranged to support meaning, not just chronology?

- Factual edit: Are dates, names, locations, and claims accurate and verifiable?

- Ethical edit: Is anyone misrepresented, exposed unnecessarily, or denied context?

- Language edit: Is the tone precise, respectful, and free from sentimentality or judgment?

The Chicago Manual of Style, widely used in historical and biographical publishing, emphasizes accuracy, sourcing, and clarity as non-negotiable standards in nonfiction revision, particularly when real people are involved.

In addition, writing centers such as Purdue University’s OWL stress the importance of revision distance, noting that writers are often too close to their material to see gaps or bias clearly.

Whenever possible, allow another trusted reader, preferably someone outside the family, to review the manuscript.

Distance reveals assumptions, emotional blind spots, and unclear explanations that insiders often miss.

11. Decide How the Biography Will Live

Professional biographers do not stop at writing—they plan for the biography’s afterlife. Where and how the work will live determines tone, length, documentation level, and disclosure boundaries.

Common formats include:

- Printed family book: Formal, archival, often conservative in tone

- Private digital archive: Flexible, expandable, ideal for documents and media

- Public memoir or blog series: Narrative-driven, selective, audience-aware

- Recorded oral history companion: Voice-centered, preservational

Archival institutions such as the Library of Congress and the Society of American Archivists emphasize that format affects longevity, accessibility, and ethical responsibility, especially when preserving personal histories.

Deciding the format early helps you answer crucial questions:

- Who will have access to this story?

- What level of detail is appropriate?

- How permanent should this record be?

This foresight separates private remembrance from intentional historical preservation.

You can explore how you can bring your characters to life.

Final Thoughts

What have you learned from these tips on how to write a biography about a family member?

Writing a biography about a family member is both an act of love and stewardship.

You are preserving truth, context, and memory for people who will never meet this person but will live with the consequences of their life.

When done with care, discipline, and expertise, a family biography becomes more than a story.

It becomes a bridge between generations.

And that is work worth doing well.

About the Author

Isaac is a multidisciplinary writer whose work spans biography, legacy writing, content strategy, and narrative nonfiction. He brings professional rigor, contextual research, and narrative intent to every project—whether documenting personal histories or crafting thought-led written work.